Elections are about a lot of things — policy, partisanship, personality (and those are just the words that begin with “p”) — but they can also boil down to a basic question: Who is fit to serve?

The definition of “fitness” is, to some extent, in the eye of the beholder. It centers on who we see representing us — our needs, our desires, and our fears. It is shaped by our biases and our proclivities. Notions of “fitness” also change over time as our society evolves.

There was a time when women weren’t considered “fit” for elected office, even by other women. Same went for members of marginalized racial groups. Slowly, far too slowly, progress has arrived, thanks to courageous pioneers who steadfastly chipped away at these prejudicial definitions of “fitness.” First at the local level, and then at the state and federal. For all the problems that ail us, including ongoing racism and misogyny, today's slate of candidates (in both political parties) suggests that most Americans are now willing to vote for people once considered "unfit" based on their race and/or gender.

Fitness in terms of health, both mental and physical, is a more complicated matter. There is a widespread belief that voters should have a sense of their candidates' health. After all, we are selecting the people who will represent us in important decision-making capacities. If someone's impairment or illness would affect their ability to fulfill the requirements of their office, there is a general belief that voters have a right to know.

The burden is not the same for all elected officeholders. Those in the executive branch, especially the president, must make split-second decisions that could mean life and death. In many cases, they are the sole decision-maker, the person with whom the buck stops. Those in the legislative and judicial branches often can carry out their duties with greater accommodation to health concerns. So perhaps for them, the stakes may be lower. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was able to serve for years after a serious cancer diagnosis. Would the calculus have been different if she had been president?

But even in the realm of physical or mental health, societal mores can change. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was mostly paralyzed from the waist down, and yet this fact was painstakingly hidden from the public. The press was complicit in this concealment. There was a belief that pictures of FDR unable to stand would convey weakness. The historical record demonstrates how preposterous this prejudice was. His leadership was strong in the depths of the Great Depression and in war. Historians to this day praise him for it.

In a sign of progress, the FDR Memorial unveiled 20 years ago features a statue of the president in a wheelchair. The Washington Post explained at the time that the monument represented the culmination of “an emotional six-year campaign led by disability advocacy groups to show the 32nd president as he lived, not as he portrayed himself to the public in a bygone era.”

A bygone era, indeed. As just one example among many: Today we may apply various criteria to judge Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s fitness for office, but his use of a wheelchair is not one of them.

Questions of mental and emotional health are more complicated, in large part because the stigmas around them are more persistent and because they are more difficult to see. Even there, however, society has evolved. During the 1972 Democratic primaries, the question of whether Maine Senator Edmund Muskie cried at a campaign event made headlines (Muskie had been targeted by a dirty trick campaign from backers of Richard Nixon). At the time, a crying politician raised questions of fitness. Fifty years later, that seems absurd.

On the other hand, once again back in 1972, Missouri Democratic Senator Thomas Eagleton dropped out as his party's vice presidential nominee just days after the Democratic Convention. The reason? Revelations that he had been hospitalized and received electric-shock therapy for depression. George McGovern, the Democratic nominee for president, feared that voters would worry a recurrence of Eagleton's depression could endanger the country. Would the same judgment be made now? And what do we make of speculation among historians that Abraham Lincoln, perhaps our greatest president, might have suffered from depression?

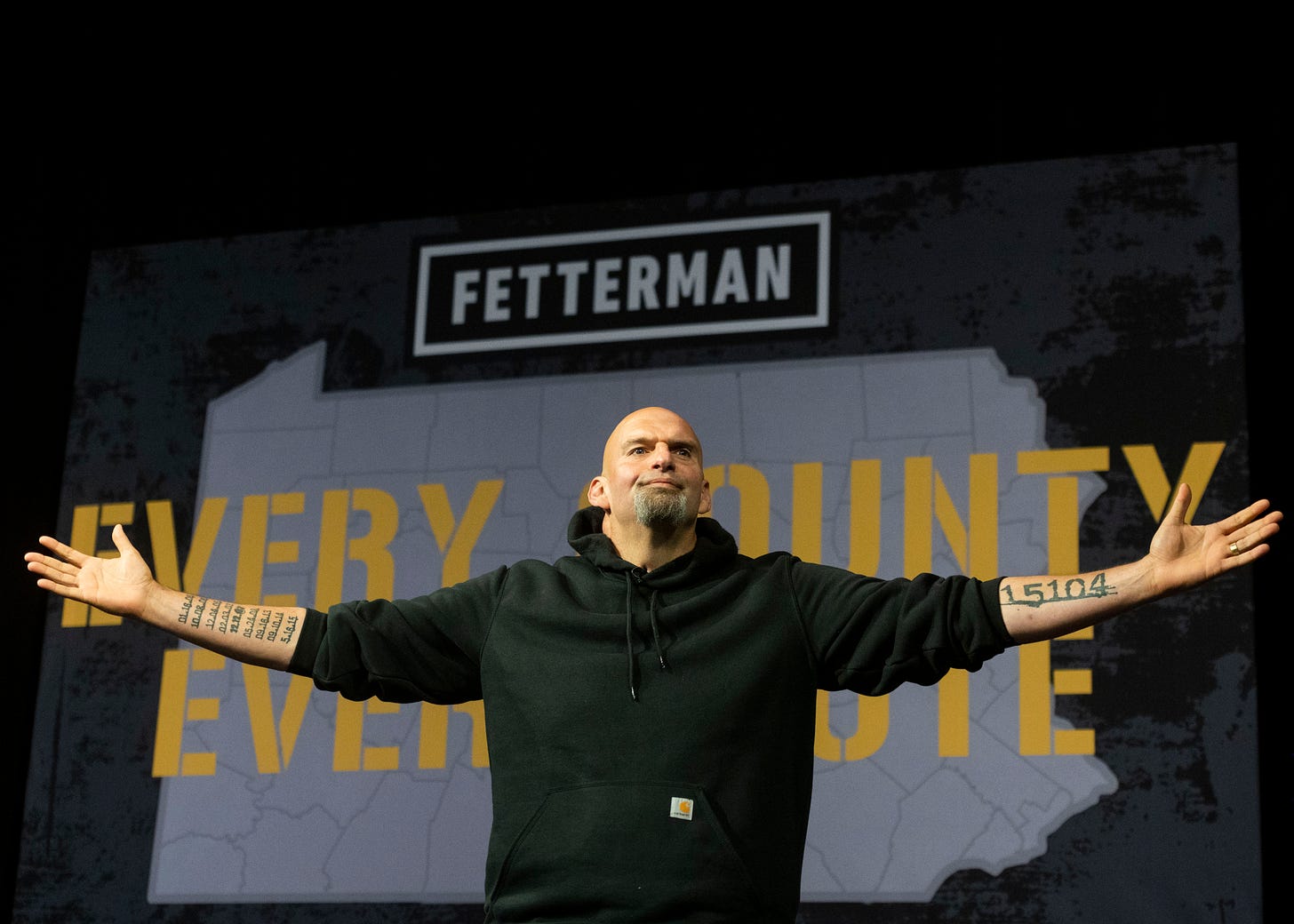

If you have been following the news, you may anticipate where this discussion of “fitness” is going. We are less than a month from Election Day, and control of both the House and the Senate is on the line. For the latter chamber, a key contest is in Pennsylvania. Democratic nominee John Fetterman once had a sizable lead in the polls over TV's Dr. Mehmet Oz, but the race has tightened considerably. After all, the Keystone State has been a toss-up for a few election cycles now.

But a central attack from Oz is whether Fetterman is “fit” to serve in the Senate following a serious stroke in May, just days before the Democratic primary. After taking time off to recover, Fetterman returned to the campaign trail but admits he is not 100 percent. He sometimes seems to exhibit a lingering problem with his auditory processing.

In a recent NBC News interview, Fetterman requested that he read the questions as they were being asked, through closed captioning technology. When the interview ran, the entire thrust of the story was Fetterman’s health and the closed captioning provisions for the interview. The footage also showed Fetterman struggling to find some words. The NBC reporter, Dasha Burns, said Fetterman had trouble with “small talk” before the interview.

This issue has now blown up. Not surprisingly, Republicans are eager to jump on this development as evidence of Fetterman’s supposed cognitive deficit. But the characterizations of the NBC News report have prompted a fierce backlash — in particular from two reporters who recently interacted at length with Fetterman.

Kara Swisher, a stroke survivor herself, noted that in her hour-long interview with Fetterman for her podcast, he was fully engaged. She said in a tweet: “Sorry to say but I talked to John Fetterman for over an hour without stop or any aides and this is just nonsense.” She added, “Listen to my interview. Even my rabidly GOP mother had to admit she was wrong.”

Rebecca Traister, whose New York Magazine profile The Vulnerability of John Fetterman deals with how Fetterman's health is being covered, wrote in a tweet, “Watching tv news/online pundits leer over clips of an interview in which he’s completely engaged and communicative is stomach-turning and a super depressing example of what I was trying to describe.”

Underlying this discussion is the progress we have made in treating strokes specifically, and serious medical conditions more broadly. Diagnoses that once would have appeared hopeless no longer are. Also, American demographics are shifting — we are aging as a society. Both factors suggest our standard of who is fit for office will continue to change.

But attacks on mental acuity still resonate. Republicans lob them in their attempts to undermine President Biden. The topic was an active source of speculation for Trump, as well.

At the same time, perhaps this idea of how we measure fitness is too limited. Are people who deny the results of the 2020 election fit for elective office? What about politicians who embrace lies, stoke division, and foment violence? Many doctors and scientists have warned that Oz, Fetterman’s opponent, has spread dangerous medical misinformation. How should that be factored into assessing fitness?

For the press, there will always be questions of context and balance. Judging medical fitness is legitimate, but are we providing the audience a nuanced understanding, or are we playing into stereotypes? What extra responsibility do we have if the main argument from a candidate’s opponent is that they are not mentally up to the job? How an interview is portrayed or edited together can shift the narrative significantly, and we should remember that as we weigh the impact of our work. We have seen the press cover up for politicians in the past. That was wrong. But so was elevating relatively minor issues through false equivalence. Are we being ableist? These considerations should always merit active discussion within newsrooms. How will the press cover the debate between Oz and Fetterman on October 25?

Governance is about the long haul, and none of us can predict the future. The Senate in particular is known for residents who stay for decades, long enough for their mental faculties to wane (as happens to most of us). How should we evaluate them?

Ultimately, it is up to us as voters to assess fitness and weigh our choices. Ideally, we’ll be careful of jumping to snap decisions or penalizing limitations that may not be relevant.

Note: If you are not already a subscriber to our Steady newsletter, please consider joining us. And we always appreciate you sharing our content with others and leaving your thoughts in the comments.

Even though I am in California, I have been donating to Democratic candidate since the primaries, a few before too. One of the first I started supporting was John Fetterman, as I saw he was dedicated, honest, and also had the guts to call a spade an f**ing shovel when necessary. He is also well educated, experienced both as mayor and Lt. Governor of PA. The stroke that he had, he is recovering from, and will continue to do so. Dr. Oz on the other hand is in this race for what? I do not see any of the qualities that Fetterman has, but rather an opportunist, publicity seeker, and a person of questionable character because of his promotion of some really out-there stuff on TV. And, he's not even a Pennsylvanian... using a relative's address to match the residency qualifications. I for one am going to continue to support Fetterman, and VOTE BLUE all the way down my ballot here in CA.

Dan, you only scratched the surface of fitness to serve. What about Hershel Walker? or Mastriano? Keri Lake? or for that matter Ron Johnson.