What Might Have Been

For this Sunday essay, I would like to take an opportunity for reflection. I know a lot is going on in the news of the present, and it is all very important and worthy of attention and focus. But there are also some touchstones of the past that well up, asking to be acknowledged. And one of our hopes with Steady is that we can provide a vantage point through which to build a community of engagement, remembering where we have come from and where we might be going, in addition to where we are at any given moment.

With this in mind, I want to remember somebody whose name and story you almost assuredly have heard. I did not know him personally, but I could have. He was a contemporary — only 10 years my junior. Yesterday, August 28th, was the anniversary of his death. He would have been 80 years old this year. He could have been. He should have been. His name is Emmett Till.

Just think about how much life is lived between 14 and 80. I do. Milestones like high school, maybe college, a first job, relationships, perhaps marriage, children, grandchildren. These are some of the many markers along the journeys of life. Emmett also set off on what he hoped would be an exciting journey, from his hometown of Chicago to visit relatives for the summer in Mississippi. He left on a southbound train and returned in a casket. Emmett’s future was brutally taken from him — all of life’s possibilities denied by torture and bloodshed. It is shocking how much he had to bear, and how much he didn’t get to see.

All this happened just 66 years ago. That’s not ancient history. I was 24 years old. This was after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, after the U.S. Military was desegregated, after Brown v. Board of Education. In the ensuing years a lot has changed, but racism, systemic injustice, and white supremacy have continued to live on — and are even experiencing a reflourshing.

We do a grave disservice to those who have suffered and died when we try to put these atrocities into the tidy archival boxes of “history.” We must confront how recent this is and how the societal ills that cut lives short and fomented fear have lived on while its victims have not. It is worth noting that even Carolyn Bryant Donham, the woman whose false allegation lead to Till’s lynching, is still living today at 87 years old.

We must not fall into the simplistic thinking that the past is past and well behind us. The legacy of discrimination, the effects of such harm and trauma, echoes through generations and has a direct connection to our present. As the recent census shows, we live in a country that is becoming ever-more diverse. That makes our collective reckoning all the more urgent and necessary. It is the very act of confronting once and for all the deep currents of racism that will keep this nation united and on a path of progress going forward.

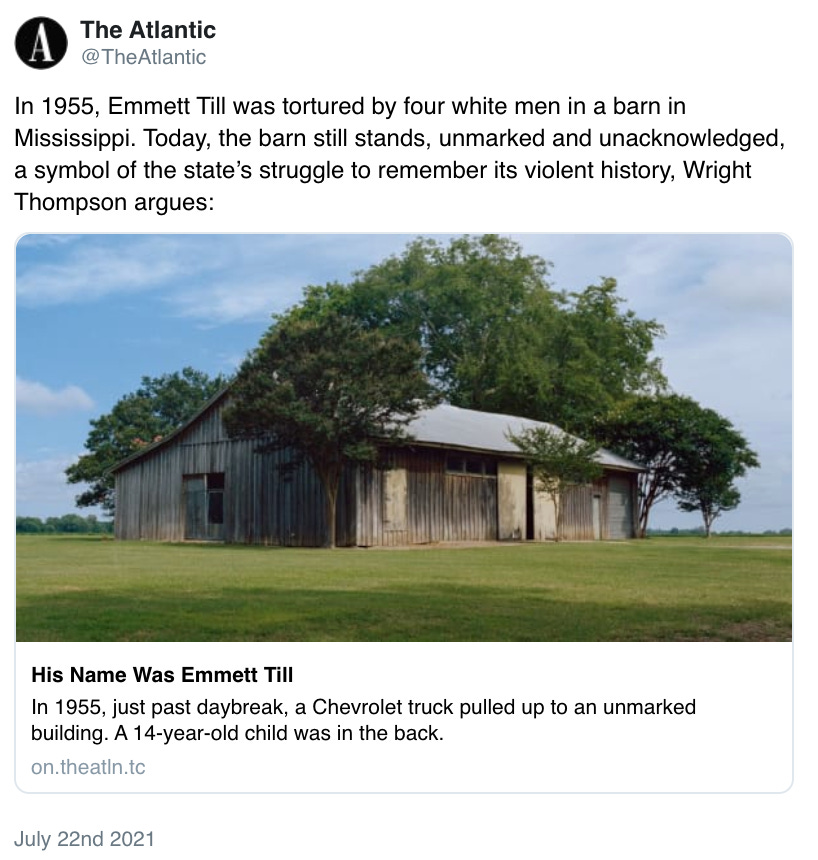

Unfortunately, instead of a national consensus around the need to own this history, to teach it and learn from it, we are seeing fights in the media, from our political leaders, and most ominously in our schools over the truth of our past, and present. Most of this is not innocuous misunderstandings. This is a deliberate effort to keep existing power dynamics entrenched, ones based on fear and a denial of the worth of others. A metaphor for this can be seen in the bullet holes riddling the Emmett Till Memorial sign. It was defaced and replaced so many times that eventually a bulletproof version had to be installed.

We must understand that America is, by the standards of other nations, still a young country. We have changed rapidly, in many ways for the better, but not fast enough. And that progress, as we are seeing today, is precarious. Those who have borne the greatest burden of the darker aspects of our national legacy, Black Americans in particular as well as Native Americans and other marginalized groups, have no choice but to live in the reality that history has bequeathed to them. They do not have the luxury or the choice to look away. And neither should anyone else.

In the wake of World War II, Germany understood that the only way to prevent violent hatred in the future is to stare unflinchingly at the horrors of the past. (That effort even has its own name, “vergangenheitsaufarbeitung,” which translates to a working off of the past.) We are in some ways inching towards that, as we remove statues of Klan leaders from the halls of government and in some places pledge to grapple with what it means for Black lives to matter. But this cannot be half measures in half the country. We all must be forced to look into the uglier corners of our history, so that we can be better, to ask what have we lost because of hate? What might have been? We are determined at Steady to return to this topic. We all need to be reminded of how we got to where we are today and what has been sacrificed getting there.

When it came time for Emmett Till's funeral, his mother faced a gut-wrenching decision. Would she shield the world from having to see how ugly hatred can be? Or would she open the casket of her only child to show his brutalized face? She chose the latter. “Leave it like that,” she said. “Let the people come to see what they did to my boy.”

(Here is a short film about her decision. Please note it contains graphic images.)

I hope to continue to build a community here on Steady. If you aren’t already a subscriber, please consider signing up to a free or paid subscription. You can also leave a one-time tip to support our work. And if you are already part of our family, please consider sharing this post — and Steady — with others.

Placing the horrific crimes like the murder of Emmett Till, and more recently, Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd just to name a few, front and center is extremely important.

For anyone who has not visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, I would strongly urge you to do so. I paid a visit there in September 2019 and I will tell you it was one of the most gutting experiences of my entire life. Every American should visit and see for themselves the rows and rows and rows of monoliths bearing the names and places of lynching victims. I am not ashamed to say I openly wept during my visit being completely undone by a wall holding jars of soil taken from some of the many lynching sites.

It would be bad enough if these murders were truly relegated to the past, but racially-motivated murders, especially those committed by the people who are supposed to protect and serve, continue to occur.

As a society, we must not remain silent, for to do so is to be complicit to the crimes of racial injustice.

Mamie Till's decision to show the world how her son had been brutally murdered took tremendous courage. It was one of the sparks that set off the chain reaction that would eventually lead to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The fight for equality continues, and the past two decades have seen our civil and voting rights which were fought so hard for be eroded. I have great concern for where we are headed if everyone does not stand up and speak out. It is not enough to just stand by and silently agree.

If we have a platform, we must use it to elevate the voices of those most marginalized, and whose messages go largely unheard. If we are white, we should not presume to speak for those of color but to instead amplify their voices and messages.

As a news editor, my job is provide context and to frame those stories around their voices in a way that will not only resonate with readers but also highlights the warp and weave of the overall fabric of the subject.

Dan Rather and the Steady team are masters at doing this and have my enduring gratitude and appreciation for their approach and hard work. Their work matters, as do the thoughts and actions they inspire in all of us who take the time to read their words and move forward with purpose and determination to do what is right.

My 30 year old son, who is mixed race including black, was discussing in a law school class about Thurgood Marshall and someone mentioned what his ancestors went through. His reply, "my ancestors? You mean my grandparents?" He's heard the recollections about how his great- grandfather had to sit up at night with a shotgun warding off the KKK in Georgia, and his grandmother a a little girl would go into the bathtub so she wasn't shot if the KKK shot into their house. This is our recent history, America.