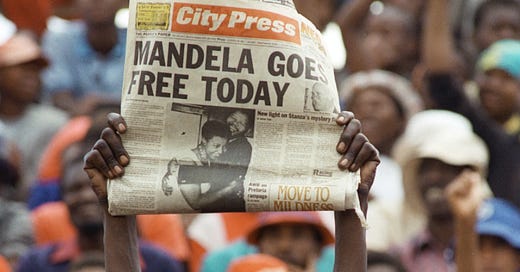

The United States is now facing one of the more divisive eras of our history. We stand, one month after an insurrectionist ransacking of the Capitol, two days into the second impeachment trial of a one-term President, and face an unknowable stretch of time fighting a vicious pandemic. At times like this I like to turn to history. I find reassurance in the context of the past —oftentimes I can find lessons and wisdom to help guide a passage into the future. My thoughts today reach back to another time and place recovering from the injuries of a deep, painful, and bloody division. February 11, 1990 is a day I remember vividly and Nelson Mandela is a man I’ll never forget.

Thirty-one years ago, I had the opportunity to meet and interview Mandela just after he was released from prison. We met at his home —a place he had not lived in for more than a quarter of a century. What struck me first and deepest was his calm, self-deprecating, and often mildly humorous demeanor. He was soft spoken, and when he spoke it was much about forgiveness and the need for reconciliation in his country. Yes, there was a time in his past when he was about violence, seeking to effect change through violent acts. But here, he spoke of the future, the power of nonviolence, and how he was determined to be of help in the making of a new and better South Africa.

I had never met a person who was more forgiving. How could a man who had been so wronged speak so eloquently and forcefully for reconciliation? And yet, Mandela saw an urgent need for reunification, renewal, and moving forward.

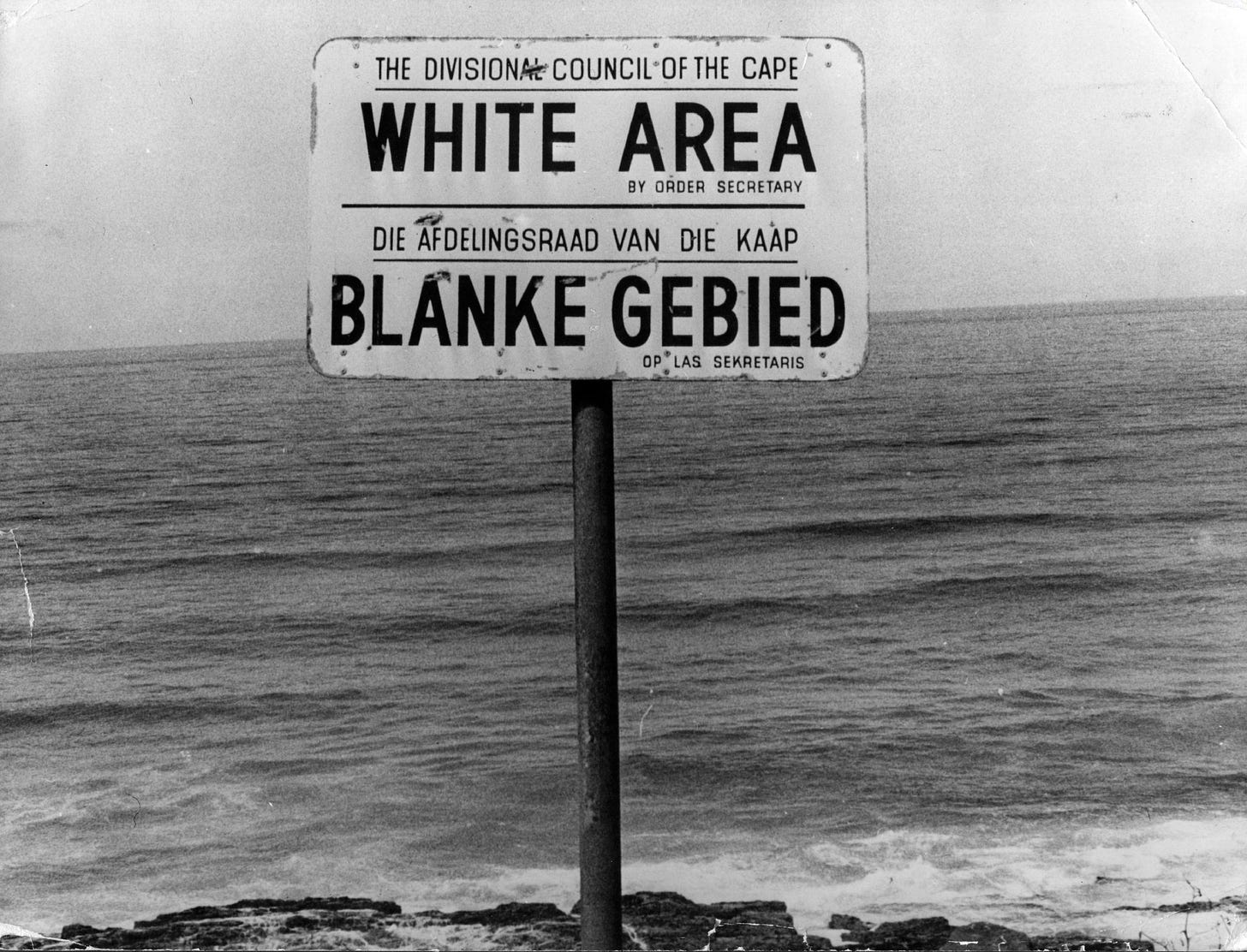

For those who are unfamiliar or were not yet of memory-age, South Africa had upheld apartheid (meaning “apartness” in Afrikaans) from 1948 to 1990. This was a system of legislation and policies that sanctioned and institutionalized racial segregation, as well as political, social, and economic discrimination against the non-white majority population of South Africa.

Under apartheid, contact between white and nonwhite South Africans was limited. Restrictive policies were enacted including, but not limited to, the establishment of separate public facilities, political disenfranchisement, the forced removal of land from non-white South Africans, and a ban on interracial marriages. A combination of protests, pressure from the international community, and new leadership began dismantling the legal basis for apartheid under the administration of President F.W. de Klerk in 1990. De Klerk (who released Mandela from prison) would continue to work with Mandela to improve South Africa. Together, they won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. And eventually ran against each other in the 1994 national election (open to all races/enfranchised for all) before Mandela won handily to become the first Black president of South Africa.

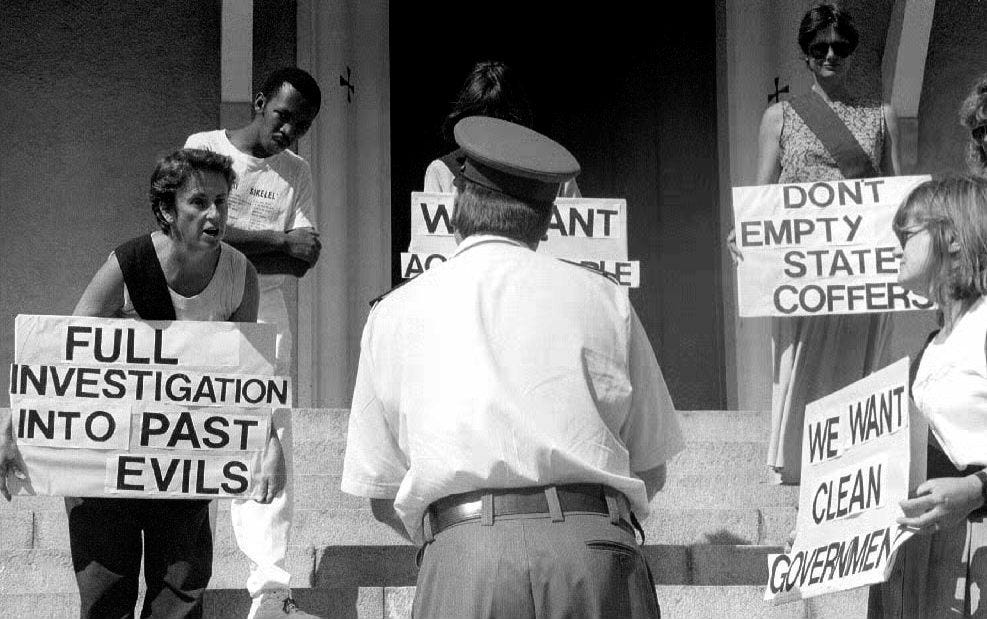

These two men, once on opposing sides, had not let bitterness get in the way of progress for their country. But it is important to note that their progress did not come without reckoning. With the help of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission —the 1995 restorative justice body aimed on gathering and hearing evidence from both victims and perpetrators of apartheid— South Africa was able to contend with and heal from its ugly history. Not perfectly, but to an impressive degree.

Now, what worked in South Africa may or may not be a roadmap for better race relations in the United States of America. But it is at the very least, worth studying for lessons applicable here in our own country. It takes hard work and an even harder look within ourselves, to put this nation on a path towards the common good. But compromise is not reconciliation. We can’t unite until we have an accounting and remedying of the national sins that have brought us to this moment.

As much as we praise Mandela for his capacity to forgive (after 27 years imprisoned), it is noteworthy that he did not forget —and neither did his country. The violence against, and deprivation of, the humanity of the people of South Africa was not swept under the proverbial rug. It was held up to the light of day and examined in such a fashion that it could not be unknown, ignored, denied, or discredited. Furthermore, it was recorded for posterity (in the commission’s final report) so future generations could learn to never make the same mistake.

When asked about Mandela, I often say that I consider him one of, if not the, greatest leaders of the second half of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st. And I believe that. Because in his determination to improve and unite South Africa, he taught us all about the transformative power of a forgiveness and reconciliation that is honest and unflinching.

Mandela would be the first to tell you he was far from perfect. And that should also give all of us hope. To be perfect is an impossible task. The very preamble to the founding charter of our nation speaks of forming a “more perfect union” —not perfect, but a path to an unattainable yet worthy goal. That’s the point. For it is in striving to be better that we become better.

I hope we, as a country, can find the discipline and wherewithal for a reconciliation that doesn’t shy away from etching in our collective memory what has been unjust, undemocratic, and inhumane in American history. To build a bridge across a divide, you need to know first, with utter clarity, the depths you must transverse. Mandela understood this. Let him be an inspiration for us as we seek our own path to truth and reconciliation.

—Dan

Our goal at STEADY to build a vibrant digital community —the more voices, perspectives, and viewpoints that can add to the conversation, the merrier. If you like what you’ve seen here, please consider subscribing and telling others to join as well.

I remember that day very clearly. I was born and lived during the almost 50 years of Apartheid in South Africa. A relative of mine was arrested and thrown into jail because she happened to be sitting on the front seat of a car, next to an Indian, who happened to be a friend of the family. So there was no reason for her to sit in the back seat.

We were invited to the family's daughter's wedding, and had to apply for permission to go. We were refused. So we weren't even allowed to befriend people of other races, let alone "consort" with them. Trevor Noah speaks about how he was "born a crime". His mother was a Zulu woman, his father a Swiss immigrant. I'm sure most people in America have at least heard of him, or follow his show. If you haven't read these two books, anyone reading this post, make the effort to find them: Born a Crime, by Trevor Noah, and A Long Walk to Freedom, by Nelson Mandela.

As a white family, we watched television with a fair amount of trepidation. Had Mr Mandela gone the Trump route and said "kill the Boer", there wouldn't have been a white person left in the country to live to tell the story of now 27 years of freedom.

Not only have we lived with freedom, but on 27 April 1994, we stood in long lines that snaked from the voting booths for so long, they had to allow people to vote the next day. My eldest son celebrated his 21st birthday on that day. He and his brother stood proudly voting for the first time, for Nelson Mandela to be our president. On that day, in a country still riddled with crime, not a single crime was reported. The police vans stood empty while white policemen, who a year before would've been ordered to shoot before asking, stood with their black co-workers waiting to be let off duty to vote. Unoccupied for two days, everything went to the new normal when Nelson Mandela was declared the virtually winner with 62.5% of the vote. Considering that a year before the Nationalist Party could've held another virtually unopposed vote, they went into a coalition with the ANC, while the official opposition became the Democratic Alliance, a party cobbled together with people of all races, and to which Mr de Klerk now belongs.

A brief personal history. When I was in high school, my two last years, I opted for a new subject because politics has always interested me. I was taught Commercial Law by Mrs de Klerk, the young lawyer married to Mr de Klerk who ran a legal practice in our town in the 1960s. Sadly they divorced and he remarried, and she moved to a small village where she was murdered in 2001.

Over the next years, Mr Mandela in co-ordination with representatives from all political positions in the country, initiated the writing of our Constitution, the most liberal one in the world. It is worth reading the rights afforded South Africans. He with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, himself more of a political voice than a religious one, set up a "Truth and Reconciliation commission" where all previous threats on every side were able to admit their faults, and crimes, and where they received, mostly, absolution. We became Archbishop Tutu's "Rainbow Nation" with a new anthem that included several of our now 11 languages, and a new flag that flies proudly over our teams when we compete against other nations in various sports and the Olympic Games.

If a country of the type of racial hatred and divisions can overcome their differences, to find what makes them similar, rather than different, with Indians, Africans, white people, Portuguese, and Italians living in the same street and reminding each other of covid lockdown curfew time by sounding noisy vuvuzelas, America and overcome its divisions, and possibly achieve that "more perfect union".

Thank you for hearing me.

And Mr Rather, thank you for telling our story.

Truth and reconciliation must start with the treatment of Native Americans. This country has never publicly acknowledged or apologized for the inhumane treatment of our original peoples. Colonization is not something that happened, past tense. It continues today and results in great harm to my relatives. As President Obama said, if you are not Native American, you are an immigrant. Let's start there.

I have long admired and trusted your work, Mr. Rather. Thank you for continuing in these uncertain times.