There has been so much upheaval, so much sadness, so many reasons to be dejected and deterred. And yet every day, across this vast and diverse country, women and men get up and set about on one of the most important tasks facing our nation —inspiring and educating our children. Whenever I feel myself sliding into despair I think about these millions of teachers dedicating their lives to the proposition that we can build a future better than our past.

The hardships around schooling during the pandemic have been well documented, remote learning for many, an on-the-fly imperfect experiment in pedagogy that was forced by necessity. Sadly, whether schools should be open to in-person learning, or not, has become yet another partisan political battle. And our educators have found themselves in the middle, sometimes even cast as villains for rightfully worrying about their safety. Meanwhile, the challenges of our present moment further amplify the inequities and injustices that have long plagued our school system.

There is so much to say about the larger state of education, and I hope to return to this topic often, but today I want to dedicate this space to my deep appreciation for teachers and educators more broadly.

I wrote the above tweet last December, as we headed into what would have been, under a normal school calendar, a week of school parties and events before a holiday break. The pandemic had upended all of that but not the indomitable spirit of America’s teachers. In September, a video of a kindergarten teacher trying to keep her young charges engaged online went viral. It captured so much of the intangibles that make teaching such a challenging job, and teachers such a special breed of people.

Despite all this hard work, all this resourcefulness, all this nurturing of young minds, we know that sadly teachers are not paid nearly enough or afforded enough respect (two sides of the same coin), especially when you consider the deep value they provide to society. So as we find ourselves at Teacher Appreciation Week we should remark that on a calendar full of observances, this one should get a lot more attention —not just a week, but every day of the year.

Over the course of my long and eventful life, I have learned and forgotten many things. But one thing that has stuck with me is the name of each and every teacher I ever had. These were the women and men who propelled me forward, who opened vistas and dared a kid from a working-class family to dream big. I was the first person in my family to attend and graduate from college. I never would have gotten that far without the teachers along the way who helped me build a ladder for personal and intellectual growth.

I wrote about this journey in What Unites Us, excerpted here:

When I entered first grade in 1937, Texas was still mostly rural, and Houston was a far cry from the sprawling metropolis it is today. William G. Love Elementary School was in one of the poorer sections of town, but it was rich in leadership and dedicated, talented teachers. All of them were women. In that period, with few exceptions, the only work outside the home open to a woman was as a nurse, a secretary, a waitress, or a teacher. And teaching was an option for only the comparatively few women who had finished college. So it is no wonder that Love Elementary, in the heart of “the wrong part of town,” was loaded not just with women, but with very smart, hardworking women.

The principal, Mrs. Simmons, was the smartest, hardest-working of them all, and she was a potent force in my early life. With the exception of my parents, she probably did more than anyone else to shape me into the person I would become. Mrs. Simmons ran her school as a kind of benevolent dictatorship. She personally hired every teacher. She knew every student’s name. She was in and out of all the classrooms every day, checking, directing, encouraging, and spreading her creed of “Love conquers all.” It was a play on the school’s name, of course, but it also formed the basis for her mantra: “We all love to learn and we love one another.”

Don’t be misled by all this talk of “love,” however. School under Mrs. Simmons was a protective place, but you weren’t coddled. She was a tough disciplinarian who had zero tolerance for any misbehavior. If you acted up in class, got into a shoving match on the playground, or disrespected a teacher, you wound up in Mrs. Simmons’s office. She would sit in her over-large upholstered chair behind her spartan desk, and you would sit on the single wooden chair before it. The Texas and American flags stood imposingly in each corner, and the mottled light filtered in through the two large oak trees behind her windows. It was the last place any kid wanted to be.

Mrs. Simmons would tell you in no uncertain terms of your punishment, and then she would call or write your parents. In our neighborhood, few people could afford telephones, and if they had a phone, they had only “party line” service, sharing their line with many other households. These phones were often busy, so Mrs. Simmons usually sent notes home. The notes would encourage (actually, require) your parents to come in for a chat. She minced no words. When she felt it was needed, she would remind you and your parents that her natural decency and kindness (her “Love conquers all”) should not be misunderstood; she could be — and, when necessary, would be — a lioness. Sometimes, to both break the ice and make a point, she would explain, “You know, there’s tough. There’s street tough — Heights tough . . . and then there is prison tough.” After a pause, she would invariably add, in a voice I can still remember, “And trust me, friends, I can be prison tough and beyond if I have to be.” She was joking, overstating, but not by much. Her talks were especially popular with fathers in the neighborhood. She spoke their language...

One of my most vivid memories from Love Elementary School was how the now-overlooked Arbor Day holiday was always a marked occasion on the school calendar. Mrs. Simmons would take a great personal interest, directing the yearly activity of planting a tree on the school grounds. Each year we would gather around to see a delicate sapling go into the soil. Our responsibilities had but just begun. We were formed into rotating teams in the months after the planting, tasked with nourishing the young trees into maturity. We took that job very seriously, an instinct I would like to think we learned from our teachers.

On a recent trip to Houston with one of my grandsons, we drove past my old school. In many ways it looked the same as when I had gone there, and as we paused for a moment I could see the echoes of my much younger self. Each school day, Love Elementary is once again filled with girls and boys who have their entire lives ahead of them. They will grow, and they will have to be nurtured. I was happy to see that five of the six trees we students planted during my time at the school remained standing. There was that marvelous magnolia. There was one of the solid oaks. I thought of what a wonderful metaphor these trees were for education. They were planted as an investment in the future. They have weathered many storms to provide shade to the generations who followed me. They stood tall, and proud. They had taken root and been allowed to thrive under a canopy of love. And so had I.

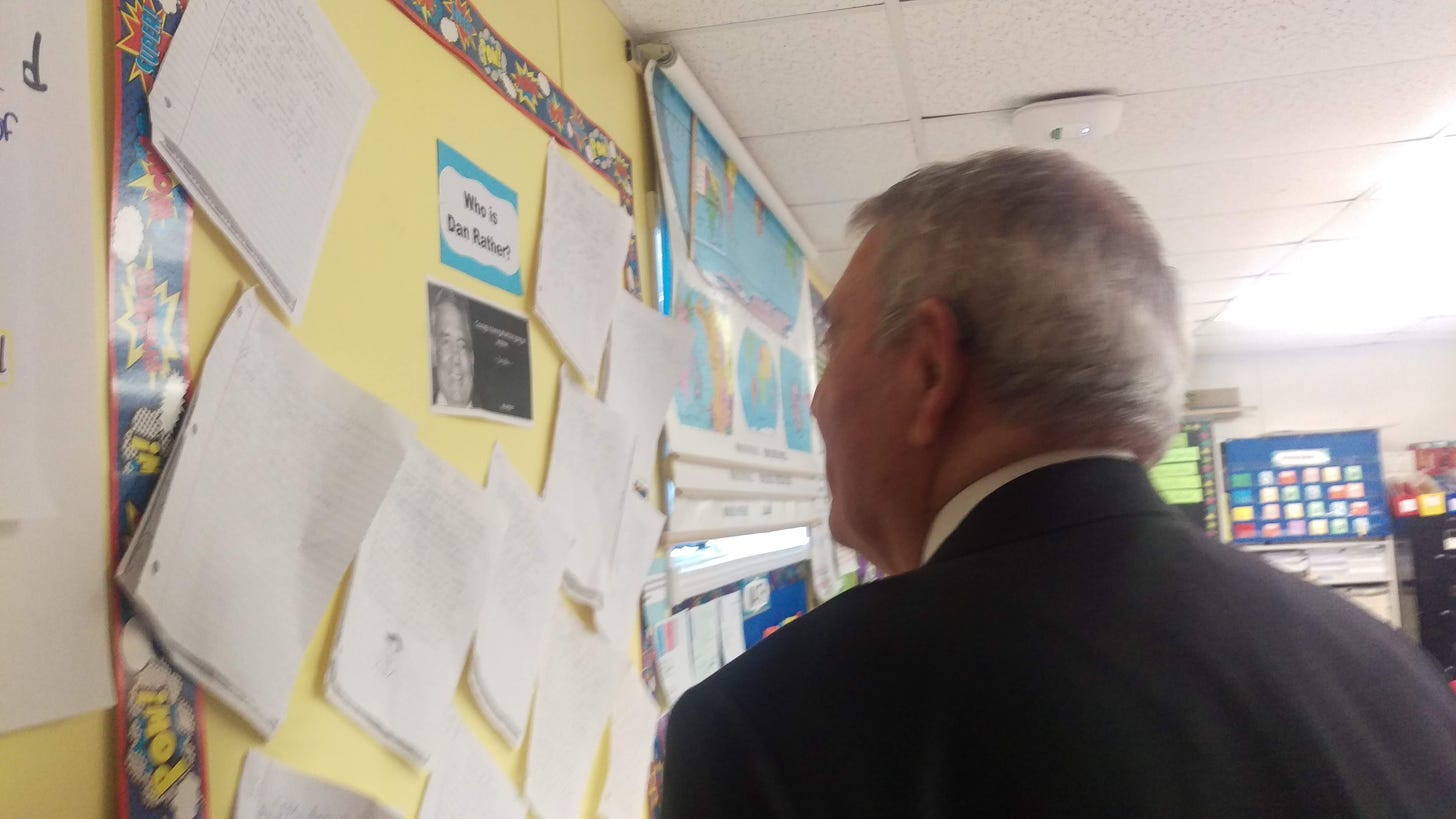

After What Unites Us was published I was invited back to Love Elementary School where I had first set foot more than 80 years ago (to write the sentence is to catch my breath in wonder at this span of time). The neighborhood has changed greatly since my youth. For one, the schools in Houston were segregated when I was a child (something I also write about in the book). Now “The Heights” neighborhood is much more ethnically diverse, much like the larger city around it, and the United States itself. But as I walked the hallways and met the children, I found so much in common with when I went there. There were the committed teachers and an inspiring principal – Melba Heredia Johnson. There was the spirit of optimism and the strong sense of community from the students and their families, many of which, as in my time, are positioned at the lower rungs of the ladder of the American Dream.

I spent time in the classrooms, where the eager young faces filled me with hope. God bless them, but these children apparently had spent some class time learning about the ancient alumnus who stood before them. Their questions and work on the bulletin boards touched my heart with humility and thankfulness. Over the course of my career, I have been fortunate to receive some tributes and acknowledgments, many more than I deserve. But this one was one of the most special.

I just wish this was where we as Americans were training our focus. If people could just come to places like Love, learn about its bilingual education, meet the inspiring staff, hear from the engaged parents, and appreciate how schools like this are so vital to building a better America we would be a lot better off. This is about community, and fairness, and justice, and hope. It’s about the belief that public education must be part of the great national spirit of equal opportunity. Educating our children – all of our children – must be part of what unites us.

The final event of my return to Love was out on the lawn. I was to help plant a young tree alongside those I had helped plant with my classmates so many decades ago. As I said my heartfelt goodbyes and left, my eyes were a bit more misty than I would have expected. I couldn’t help thinking that this world would be doing a lot better if there was a bit more Love.

A year later, I was back in Houston, with a visit to my old high school. There I got to meet the school’s valedictorian, the remarkable Emily Ramirez. The daughter of an immigrant to the United States who has since joined her older sister at a little college up North called Harvard. In their story, like so many others, we can see the best of this nation.

So thank you. Thank you to the teachers who inspired me, now all long gone. Thank you to the teachers who shaped my friends, colleagues, children, and grandchildren. Thank you to the teachers who are striving, day after day, to keep the best of America on track. Thank you for your hard work, your dedication, and your perseverance. Our nation owes you our deepest gratitude, and a lot more support. Your service, at least in the estimation of this old reporter, is of the highest order.

Steady.

—Dan

This made me misty eyed. I sit here remembering my first grade teacher and her gentle kindness toward a terribly abused, frightened child. She was the first person who made me think I might not be the waste of space I was told I was every single day at home. She made me feel something that I did not know what it was until I was older - she made me feel like I mattered to her. One day she asked each of us what we liked about school and she patiently waited while I squirmed, incredibly frightened at needing to speak up around other people. I managed to choke out that I liked to read and to take spelling tests. I ducked my head and waited on her to berate and mock me but instead she smiled and handed me a book she said I might like. I almost burst into tears at such acceptance and kindness.

Those tiny sparks of light were everything to me. I thought of her on my first day of college, each time I made the Dean’s List, as I stood in the door of a C-130 preparing to make my first jump during jump school; during each first that I have accomplished in life I remember her kindness and encouragement. I was able to thank her before I left for the military many years ago but I so wish she were still here so I could thank her again.

I cannot tell you how much your writing about teachers touches me. I retired after teaching English for 30 years in a public high school in southwest Ohio. I loved my job. I am still in touch with some colleagues with whom I worked and with many students that I taught over those 30 years. Teaching is the best, hardest, most frustrating, and most rewarding job in the world. I am so blessed to have worked in a profession I loved. Thanks for a concrete reminder.