Tulsa...

It’s been a century since a race massacre killed hundreds of Black residents in the Oklahoma city and destroyed their prosperous neighborhood which they had built with pride, resilience and hard work. If you have been anywhere near the news this past week, you undoubtedly have heard the stories through countless articles, television reports, and Internet commentary. It is a tale of outrage and woe — not only because of what took place on those bloody days of 1921, but because of what happened afterwards. Or more importantly what didn’t: an accounting with the truth.

I wanted to raise this today in our Sunday essay to get at some fundamental realities about the way we tell our American story, to our children, each other, and ourselves. The fact is that for many decades the Tulsa massacre had been largely absent from our classrooms and our history books. If it was included at all, it was merely a footnote. We need to understand why, and why this isn’t the only overlooked chapter of our history.

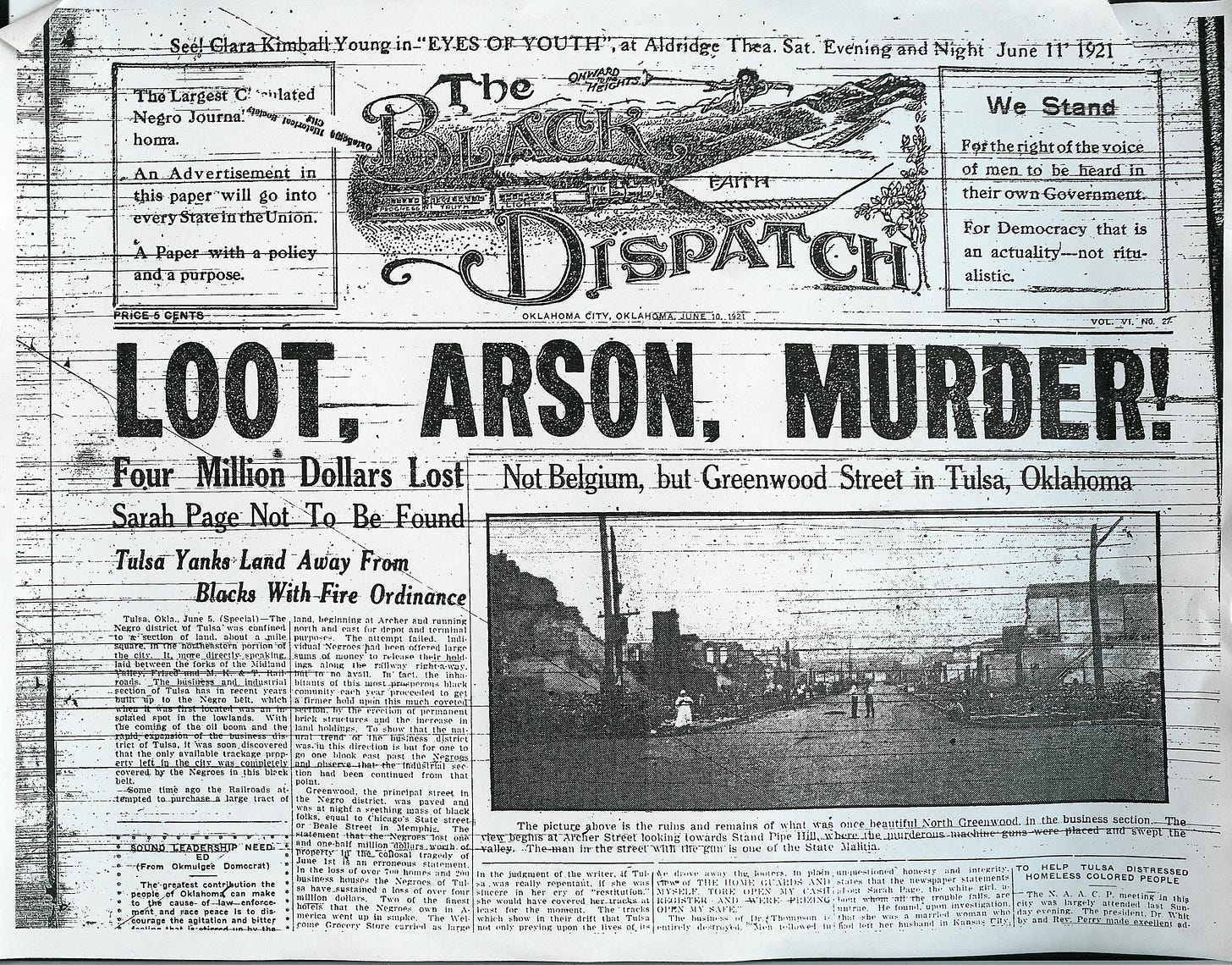

Many are just finding out about Tulsa’s prosperous Black community of Greenwood (nicknamed “Black Wall Street”) and how it was destroyed in a matter of hours by White townspeople bent on bloodshed. This is a stark reminder: we have holes in American history. Not literal holes, of course —these events certainly happened. But holes in our knowledge, our education, and our national collective consciousness.

We are living in a time where we are seeing cynical attempts to bury the past on many fronts. Even as the world marks what happened in Tulsa, a movement is afoot in my own beloved home state of Texas and many others to stifle the teaching of racism in our classrooms. It is being pitched under the new bogeyman for the political right —so-called “critical race theory”— and educators and historians are deeply worried that it will have a chilling effect on our ability to teach future generations about the forces of hate and bigotry that have played, and continue to play, a significant role in our country’s political, economic, and social systems.

The political movement pushing this historical amnesia isn’t limiting their efforts to the more distant annals of the past. It’s been five months since insurrectionists stormed the Capitol and most of the Republicans in Congress have just voted to try to erase a full accounting of what took place. The same thing is happening around the pandemic. Yes, the truth can be uncomfortable. It can challenge the image we wish to create for ourselves and our nation. It eats away at myth-making and simplistic narratives. But acknowledging history - a full and complete history - is more than just bearing witness to what took place in the past. It is the only way we can understand the forces that shape our world today.

The entire mantra of Make America Great Again was built on a literal whitewashing of our past (I am tempted to write it as “White Washing”). It is an attempt to say that America was a better place when it was more discriminatory and there were fewer opportunities for marginalized groups to have the opportunities of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This saddens me on many levels. It minimizes the violence, pain, and suffering that has defined America’s tortured journey on racial equality. It promotes a worldview where the very notion of truth is sanitized into false narratives. And it also robs our history of its own sources of strength.

The story of our nation, in all its full complexity, is the story of interwoven narratives —of tragedy and triumph, hope and despair, cruelty and empathy. When we eliminate the negative chapters we also eliminate many of the positive ones. When we ignore the villains we also overlook the heroes. To paper over what happened in Tulsa is to also write out of our history books what the Black community there was able to build in the face of great headwinds of bigotry. It is to ignore the resilience that the survivors had no choice but to summon forth. It is to ignore that our nation has been made better through its diversity, our culture enriched, our democracy strengthened, and our moral compass pointed more firmly on a North Star of progress and justice.

There are so many other stories like Tulsa where the ripples of history still shape our nation. So many groups of people have been made to feel like outsiders —they have felt the deep hurt and often physical pain of injustice. We can start with the Native Peoples of this continent. We must teach their many stories of loss. Their narrative is much more that of the Trail of Tears than greeting-card versions of Thanksgiving. Yet these tribes have fought to survive. They have strived to pass their culture and language to their children. They have etched out pride. We must not only view them for what they have suffered but for how they have endured, how they have made America better. You can say the same of so many groups, religious and ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ community, the disabled, to name a few. All of these groups have their own chapters that have been dismissed for far too long. The bigotries of American society still plague all those who have been marginalized in some form. But again, we must recognize the strength, ingenuity, and resilience that have allowed these communities to not only survive, but to flourish.

Of all the tributes this past week in Tulsa, and around the country, of all the thoughtful and emotional speeches, the detailed documentation of the loss and destruction (links I will share below), the debate over reparations and appropriate atonement, the cumulative acknowledgement that this will be one chapter no longer forgotten, there was one scene that moved me perhaps the most. It centered around three survivors of the massacre, and a whole lot more. And it involved a song I had heard many times covering the Civil Rights Movement.

With these emotional verses, the ties of the present, the past, and a more distant history came into sharp focus. We are bound as a people by a journey we have no choice but to make together. And the fact that there is still in our America a march of progress is a testimony to all who didn’t break. May we work to make the world a better and more just place, remembering and honoring those who are no longer here to march alongside us.

—Dan & Steady Team

P.S. The first step in mending the holes in our history is awareness. Below are links for further reading. We invite you to engage with an open mind. Please let us know your thoughts and feedback in the comments section below.

At 107, 106 and 100, Remaining Tulsa Massacre Survivors Plead for Justice [NYTimes]

Tulsa race massacre at 100: an act of terrorism America tried to forget [The Guardian]

Please consider subscribing to STEADY, if you have not already. Our goal is to build a vibrant digital community —the more voices, perspectives, and viewpoints that can add to the conversation, the merrier.

As a Black Latina woman, let me just say, that I wish there was more outrage from White folk. I wish more White people would be appalled, saddened, hurt, pained, gutted in spirit, torn and devastated by learning this truth about our country, our past and yes, hiding it. I'm tired of the kind words, and the hope-filled "righting of wrong-doing" BS. Honestly, I'm tired of white folk not being more upset about the cruelty. The cruelty! I'm devastated by all that I've learned. All that I never even knew. It is NOT good enough for White folk to be mildly upset anymore. That's what I'm missing in all of this. When I watch how people are erasing Jan 6th or trying to re-write Trump and Covid, I'm confused as to why White folk aren't up in arms! Where is the urgency to fix what's broken? And I'm sorry, I can't fix it, because I'm still trying to pick myself up off the floor from learning THAT YET AGAIN, there has been even more cruelty and more barriers put up against me, pushing me down, all these years. And I'm still crying. Do you understand how different our country would be had Black folk been allowed to succeed in Greenwood? Imagine a country where it wasn't burned down? Imagine a world - the healing -- if we'd even just told the truth of what happened. There's a respect in doing that. But instead, we hide and bury things so White folk can always feel good? I'm perplexed. We need White folk to take up this fight. And I just don't understand why you're not more upset about all of it? Aren't you embarrassed for our country? Aren't you confused as to why we'd be this horrible to another group of people? Are you mad that it's actually a pattern of how we function as a nation? Aren't you on fire about what the GOP is doing now? I honestly don't get it. I have never, in all my life, been more embarrassed, humiliated, disgusted and appalled at being an American of this country, the United States. We are so much better than this...at least I thought we were. I don't know what it's like to be a White person in this country. I have no idea. But I'm telling you, this isn't going to work if your goal is to just be "aware" of things. I need an essay on how to fix it. I need White folk to write essays and tweets and comments on what they will do to fix US. The United States. Mr. Rather, this comment isn't just to you... it is not. You are a national treasure. But it is only because of your essay, your incredible art and love of this country that I feel comfortable right now, in tears sharing this... I just thought we were a better country is all. And honestly, I don't know how these Black folk continue being full of love and joy, singing with hope... because I'm heart-broken really. I'm devastated. I used to love my country anyways - in-spite of so much, but this...this just broke me.

As my friend, historian Sam Collins, is fond of saying "tell all the history." Much of it is is not what we have been taught. But, we need to know it if we are to break free from the chains it has wrapped around our understanding. In doing so we can then be freed to work towards a better, more inclusive, more truly equal future.