I think you will find my Steady co-writer Elliot Kirschner’s perspective as a parent of young children a thought-provoking and heartfelt examination of our precarious moment.

— Dan

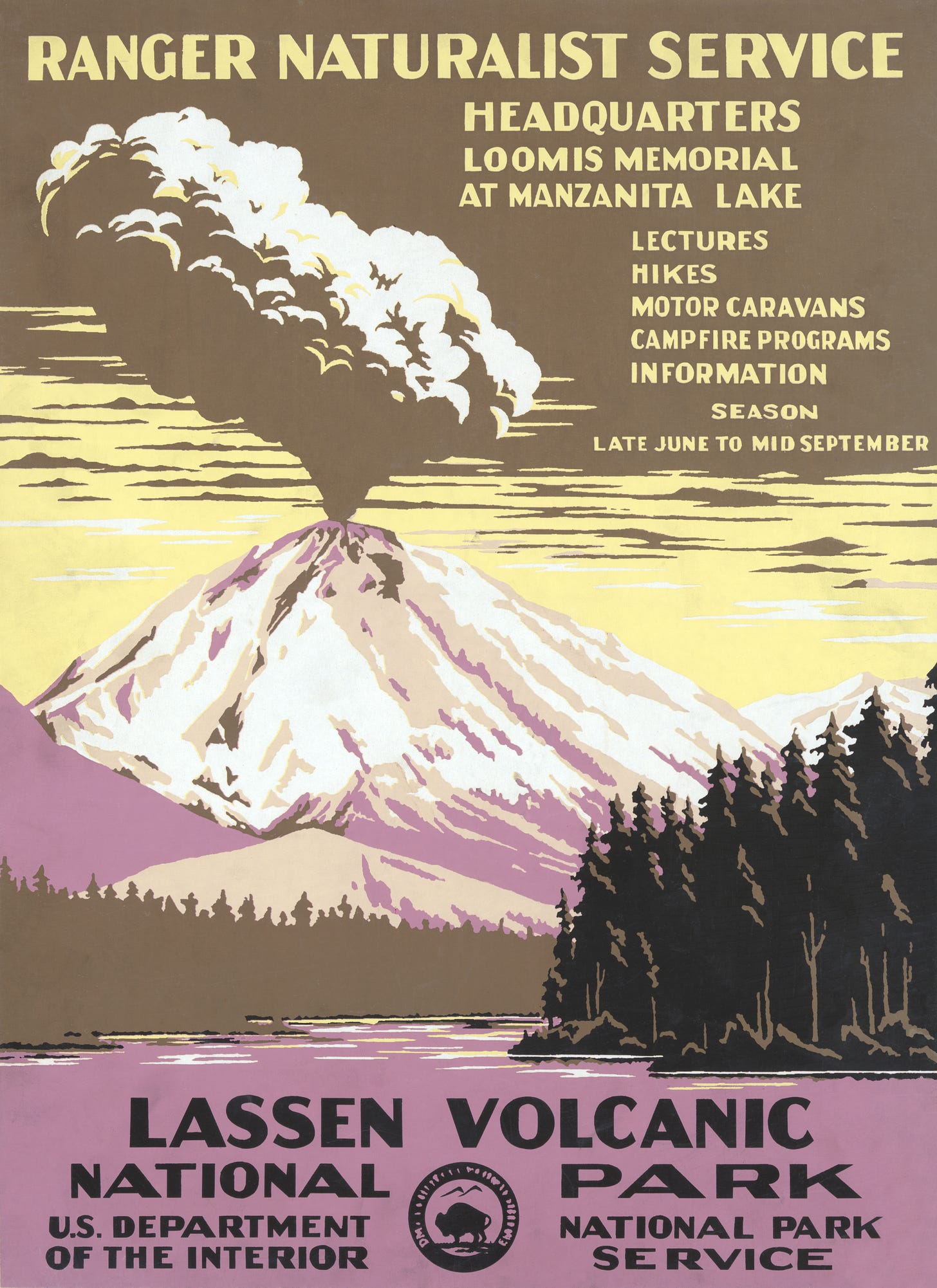

Every summer, over several years of childhood, my brothers and I would pile into the old station wagon and make our yearly summer vacation trek with our parents from our home in San Francisco up to a camp at Lassen National Park. It was a ritual, down to a stop at the same Burger King in the town of Chico for a rare fast food treat. But the real treat was ahead of us, a week of hiking and horseback riding through one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

For those who have never been to Lassen, or maybe haven’t even heard of it, it is one of the true gems of the National Park system, although far less famous than its cousins like Yellowstone and Yosemite. It’s a place shaped by an active volcano, Lassen Peak, which last erupted a little over a century ago, and all the geothermal activity that goes with it. Its streams, lakes, meadows, and forests teem with wildlife and vistas both epic and intimate. As much as the sights, I remember the smells. Around the bubbling mud baths came the pungent odor of rotten eggs from the hydrogen sulphide rising from the bowels of the earth. But in the forests, the smell was sweet and full of life, a blend of the numerous species of trees.

If you were anywhere near Lassen this summer, however, the smell was one of thick smoke and the death of much of what I remembered. Early reports are that more than half of the park was consumed by what is being called the Dixie Fire. When I called my mother to tell her she started crying.

Wildfires are once again ravaging the American West this summer, although their locations and the wind directions have meant that most of the region’s major metropolitan areas have been spared some of the smoke and punishing air quality of last year — at least so far. We still have a long way to go yet in the fire season, which now stretches much longer than it used to. Regardless, the trendlines are clear, fires are burning earlier, longer, faster, hotter, and at higher elevations. The pace and expectations of my childhood, of what summer is like outdoors in California’s natural wonder, are gone. It’s another casualty of our global climate crisis. Going forward, it seems inevitable that smoke will always be part of our summer rituals. This certainty is powered by uncertainty; the nature of wildfire is it can spring up anywhere, without warning.

My children are learning in school about the history and ecology of their adopted home state. They understand that fire has always been part of the landscape and that native peoples were wise stewards of the land who often would protect the health of forests through prescribed burns. It’s an approach that modern science is only recently and belatedly embracing. For decades the approach was to suppress all fire, allowing for tinderboxes of fuel to build up. This is one reason fires have gotten worse. But by far the biggest culprit is something my children are also learning a lot about, our rapidly heating world.

Out West the climate crisis means increased droughts which turn even high-altitude forests into torch fuel. In other parts of the country, the effects are of course quite different. While we are praying for rain, swaths of the eastern half of the country are getting far too much of it. The scenes out of Louisiana, then up through the interior, and out to New Jersey and New York and the rest of the Northeast are heartbreaking. If only we could take some of that water out here. If only we could restore more of a sense of balance. If only we had done a better job of preparing. If only we were doing more now.

I think of the years when I lived in New York, where our kids were born. Seeing the floodwaters brings back memories of what lies underneath — playgrounds, parks, subways, and street life. My heart aches for all who are suffering. I can’t help but think there is nowhere that is predictable anymore, nowhere that is safe. Now to be sure, there have always been natural disasters. Safety is an illusory concept. All our lives will end in some way at some time. No matter how much we want to try to shield our children from this knowledge, the world is dangerous. Life necessitates death.

And yet there is something different about the climate crisis, because it is we collectively who are responsible. These are acts of nature made worse by the actions of humans. We add to the danger each and every day by the systems we use to move ourselves, house ourselves, feed ourselves, and entertain ourselves. A major byproduct of our modern lives is more greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere. And our children know this. They know what they are inheriting. They know they were born into a world of greater uncertainty, a rigged game they have no choice but to play and to try to end the string of losing hands. They know the best they can likely hope for is to make things less bad — not necessarily much better.

Despite these odds, I find a lot of hope in the next generations. I have found they view life with more steel-eyed reality than I did at their age. They are very aware of the problems of this world. A global pandemic has only sharpened that knowledge. They ask a lot about what life was like, and find it hilarious that you had to watch a TV show in real time or answer a phone stuck to a wall. They are still able to keep a sense of humor while they also talk about how much of a mess they are inheriting and how much work they will have to do to fix it.

You hope as a parent to protect your children, but I think they will end up doing a much better job of protecting us. They have no choice but to live in the present. This is their moment. They can’t bemoan a past that is distant to them, ancient history. What they want is not excuses, but action, and I suspect they will organize and vote accordingly.

We are not powerless. Humans are an adaptable species. It’s why we could live in the arctic and the tropics, in oceans and in deserts. We will have to make hard difficult choices about how to engineer our future. But we can take some comfort that the levees in New Orleans held. Many of the measures in New York installed after Hurricane Sandy held up as well. But will it all continue to hold, and how much more there is to be done. The wake-up call to the truth about our ailing planet has come faster and more sudden than many of us were expecting. We must recognize that the marginalized will be hurt the most. We must do whatever we can to protect those generations yet to come. They will not have the privilege of yearning for our past. So we owe it to them to think more about the future. Our memories of what the world was cannot be an excuse for inaction. It must propel change.

One of the news reports about the fires in Lassen noted: “While seeing portions of the burn inside Lassen is upsetting, park officials emphasize that the entire region was once covered in volcanic ash and rock, and that the resilient park will eventually recover.” It’s an important perspective and a reminder that I cling to for inspiration. My children will not get to see the park as I remember it. But that doesn’t mean they can’t see the land in a new light. Perhaps if we do the work, if we can embrace the change that is so necessary, they might one day bring their own children or grandchildren to Lassen and celebrate a story of rebirth.

I hope to continue to build a community here on Steady. If you aren’t already a subscriber, please consider signing up to a free or paid subscription. You can also leave a one-time tip to support our work. And if you are already part of our family, please consider sharing this post — and Steady — with others.

Beautiful writing about a difficult and frightening situation. Your voice is essential to this newsletter, Elliot.

Elliott, excellent commentary. In keeping with the Western perspective, have you given thought to the mass removal of our wild horses from the ranges across Oregon, Wyoming and other states by the Bureau of Land Management in favor of the livestock industry replacing those thousands of horses with four times the number of sheep and cattle? Where the horses help maintain and sustain the vast grasslands of their ranges, livestock does just the opposite. It would be greatly appreciated if you, Dan and the team consider our wild horses, their mass roundups with many in dirt lot holding pens for decades and extermination. The horses are an iconic symbol of the vastness of our Western expanse but soon they will no longer exist.

Thanks,

Fran